Key Take-Aways

- 1 in 5 patients has peri-implantitis

- Damage caused is irreversible

- Disease is device-related

- Zero Peri-Implantitis Concept designed for prevention

- Proof in long-term studies

A large-scale systematic study review evaluated the prevalence of peri-implant diseases by meta-regression analysis. The result: One in five implant patients (22%) suffers from peri-implantitis and almost twice as many (43%) from peri-implant mucositis, which develops into peri-implantitis if left untreated.[1]

Peri-implantitis causes irreversible damage: Although various therapies exist (surgical and non-surgical), which can temporarily eliminate the inflammation, they all fail to achieve complete re-osseointegration over the initially exposed implant surface.[2-4]

Peri-implantitis: A public health concern

The European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) concludes: Peri-implantitis represents a growing public health concern due to its high prevalence. Managing peri-implantitis is challenging, unpredictable and associated with significant morbidity.[5]

A recent survey by Straumann reveals a similar result, with almost half of the respondents (46%) naming peri-implantitis management their “greatest clinical challenge.”

Why does peri-implantitis develop?

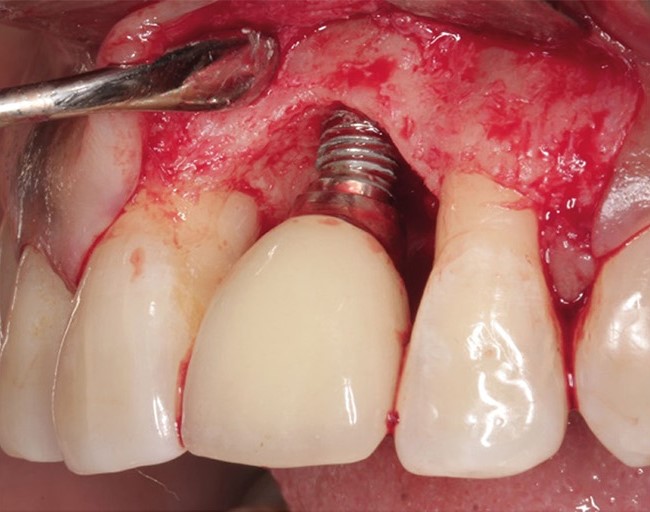

Fragile adhesion

Smooth, machined, or polished surfaces of transmucosal implant components cannot form a strong bond with the surrounding soft tissue—achieving only a “fragile adhesion” at best (Fig. 1 below, left). Plaque gradually migrates downward along these surfaces and easily breaks through this weak connection (Fig. 1 below, right), allowing bacteria to enter the soft tissue and cause inflammation.

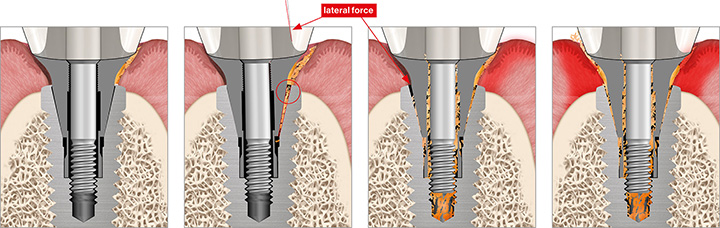

Screwed connections: Never 100% sealed

Screw-retained implants always exhibit a microgap at the implant-abutment connection, which widens under lateral force. This allows bacteria to penetrate the implant’s internal connection and colonize hollow spaces within the system.[6, 7] Over time, the bacterial load leaks back into the surrounding tissue, causing chronic inflammation and progressive bone loss (Fig. 2 below).

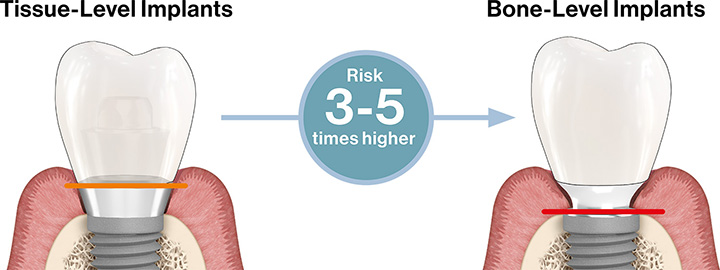

Position of the microgap

The position of the microgap influences the risk of peri-implant diseases (Fig. 3 below). Microgaps at intratissular levels, i.e. in the hard and soft tissue regions, always negatively affect the long-term biological performance of implants. However, differences exist: while tissue-level implants have shown reliable performance, inflammation can still occur due to the gap within the soft tissue.[8, 9] In contrast, bone-level implants—placing the gap at or below the crestal bone (the “danger zone”)—carry a three to five times higher risk of peri-implantitis.[10-13]

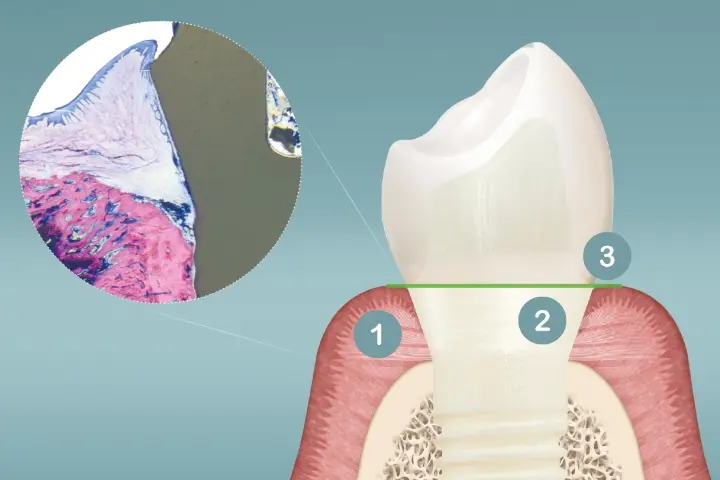

Zero Peri-Implantitis Concept

The Patent™ Implant (Fig. 4 below) was invented to eliminate precisely these risks. This advanced system has shown in studies that it is possible to have no peri-implantitis around implant restorations over the long term. Key is its Zero Peri-Implantitis Concept. This innovative implant concept comprises three core elements which work in combination to prevent plaque bacteria from penetrating the soft tissue and colonizing inside the tissues:

1) Strong soft-tissue bond

2) Transmucosal implant design without microgaps inside the tissues

3) Bacteria-proof connections (thanks to advanced adhesive technology)

Proof in long-term studies

Long-term studies at universities in Germany and Austria observed two-piece Patent™ Implants over 9 and up to 12 years of function.[14, 15] The remarkable finding: the implants showed no peri-implantitis—even in compromised patients with risk factors such as diabetes, cancer, periodontitis, poor oral hygiene, and smoking.[15] Plus, the incidence of peri-implant mucositis was notably low, with 13% at the implant level and 10% at the patient level.

These results demonstrate that, with the latest technology, dentists can drastically reduce peri-implant mucositis and entirely avoid peri-implantitis.

Study References

1. Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42 Suppl 16:S158-71. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12334

2. Renvert S, Polyzois I, Maguire R. Re-osseointegration on previously contaminated surfaces: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20 Suppl 4:216-227. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01786.x

3. Subramani K, Wismeijer D. Decontamination of titanium implant surface and re-osseointegration to treat peri-implantitis: a literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012;27(5):1043-1054.

4. Schlee M, Naili L, Rathe F, Brodbeck U, Zipprich H. Is complete re-osseointegration of an infected dental implant possible? Histologic results of a dog study: A short communication. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1):235. doi:10.3390/jcm9010235

5. Herrera D, Berglundh T, Schwarz F, et al. Prevention and treatment of peri-implant diseases-The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50 Suppl 26(S26):4-76. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13823

6. Zipprich H, Weigl P, Ratka C, Lange B, Lauer HC. The micromechanical behavior of implant-abutment connections under a dynamic load protocol. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20(5):814-823. doi:10.1111/cid.12651

7. Zipprich H, Miatke S, Hmaidouch R, Lauer HC. A new experimental design for bacterial microleakage investigation at the implant-abutment interface: An in vitro study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016;31(1):37-44. doi:10.11607/jomi.3713

8. Rompen E. The impact of the type and confi guration of abutments and their (repeated) removal on the attachment level and marginal bone. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5 Suppl:S83-90.

9. Laleman I, Lambert F. Implant connection and abutment selection as a predisposing and/or precipitating factor for peri-implant diseases: A review. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2023;25(4):723-733. doi:10.1111/cid.13185

10. Derks J, Schaller D, Håkansson J, Wennström JL, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. E ectiveness of implant therapy analyzed in a Swedish population: Prevalence of Peri-implantitis. J Dent Res. 2016;95(1):43-49 doi:10.1177/0022034515608832

11. Katafuchi M, Weinstein BF, Leroux BG, Chen YW, Daubert DM. Restoration contour is a risk indicator for peri-implantitis: A cross-sectional radiographic analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(2):225-232. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12829

12. Rokn A, Aslroosta H, Akbari S, Najafi H, Zayeri F, Hashemi K. Prevalence of peri-implantitis in patients not participating in well-designed supportive periodontal treatments: a cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(3):314-319. doi:10.1111/clr.12800

13. Yi Y, Koo KT, Schwarz F, Ben Amara H, Heo SJ. Association of prosthetic features and peri-implantitis: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(3):392-403. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13251

14. Brunello G, Rauch N, Becker K, Hakimi AR, Schwarz F, Becker J. Two-piece zirconia implants in the posterior mandible and maxilla: A cohort study with a follow-up period of 9 years. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2022;33(12):1233-1244. doi:10.1111/clr.14005

15. Karapataki S, Vegh D, Payer M, Fahrenholz H, Antonoglou GN. Clinical performance of two-piece Zirconia dental implants after 5 and up to 12 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2023;38(6):1105-1114. doi:10.11607/jomi.10284